Ocean Kin: What Whales Teach Us About Connection

- Danny Petrie

- Jun 22, 2025

- 3 min read

There are stories older than language.

You hear them if you listen - not with your ears, but with something deeper. A stillness in the chest. A hum beneath your feet when standing by the sea. A knowing that doesn’t need to explain itself. These are the stories whales carry.

Not cargo. Not soundbites. But memory, stitched into flesh and salt.

Whales Remember

Each year, whales return to the same migratory routes, the same birthing grounds, the same feeding zones - as if retracing invisible lines across a living map. Calves born in warm northern waters will travel south, then north again, repeating this cycle for decades, following paths passed down through their mothers.

This is not instinct in the way we were taught in school - automatic and emotionless. It’s something else. Cultural memory. Whales inherit not just direction, but knowledge. And in doing so, they create a kind of family lineage of place.

In this, they are not so different from us.

The Language of Longing

Humpback songs travel thousands of kilometres - deep, mournful melodies that shift slightly each season. Biologists say these songs evolve. A pod on one side of the ocean can pick up a new phrase from another, integrating it into their own vocal patterns like a remix passed between artists.

Each whale becomes both singer and listener. Memory and innovation blend. Sound becomes kinship.

Some researchers believe whales use these vocalisations not just to mate, but to keep in touch across vast distances. Like calling home across time zones.

And what is that, if not love?

Family Beneath the Waves

Whales form bonds that last beyond the breeding season. Some species travel in matrilineal pods - mothers, aunts, calves, and cousins swimming together. They care for the young communally. They mourn the dead.

There are stories of whales carrying lost calves on their heads for days. Of orcas refusing to leave a dead relative. Of dolphins - cousins in the cetacean family - bringing food to a sick podmate or helping injured whales to surface for air.

These are not gestures of survival. These are gestures of connection.

Indigenous Knowings

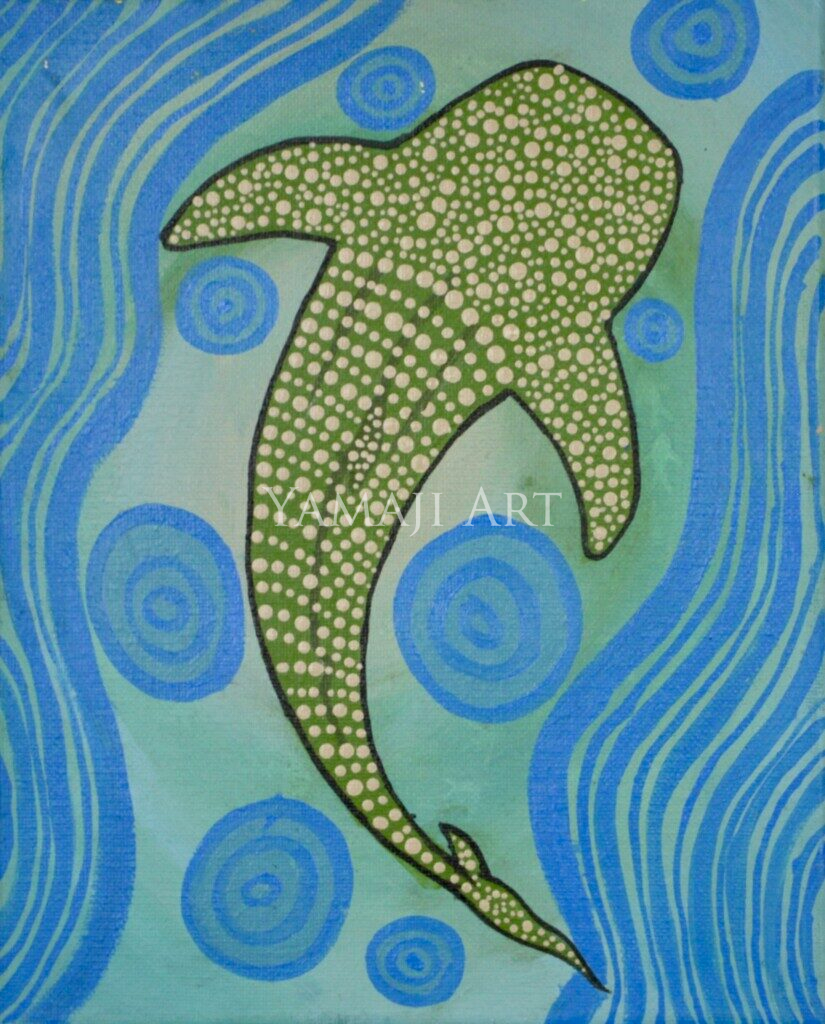

In many First Nations cultures, whales are not just animals - they are ancestors, teachers, messengers. Among some Yamaji people in Western Australia, the whale (or Maali) is a totemic figure - linked to stories of migration, seasonal change, and songlines that echo both in the earth and the sea.

These aren’t myths. They’re another way of telling truth.

We lose something when we forget this: that science and spirituality, ecology and emotion, are not enemies but old friends. The whale does not ask us to choose between them.

It only asks that we listen.

Kinship, Not Ownership

When we look at a whale, we’re not looking at a resource. Or a tourist attraction. We’re looking at a relative from a parallel world - a being whose life rhythm dances with the tides and the moon.

They don’t need us to teach them how to live. But we might need them to remind us.

Of care. Of patience. Of returning - even when the road is long and full of silence.

How We Can Honour Ocean Kin

Learn their stories: Read, listen, and amplify First Nations perspectives.

Protect their homes: Advocate against seismic testing, overfishing, and plastic pollution.

Be a gentle visitor: If watching whales, do so with humility and space.

Teach the next generation: Help children see whales not as curiosities, but companions.

Hold space for wonder: Don’t rush. Let awe take its time.

Final Echo

Whales are not just passing through Geraldton. They’re returning. Like we do, when we seek meaning. When we revisit places of significance. When we remember who we are in relation to others.

Maybe the most important thing the ocean teaches isn’t about whales at all. Maybe it’s about kinship. And how to carry it, gently, wherever we go.

Comments